Mechanics to Metaphor: An Astrology of Vibration

An Astrology of Vibration. The notion of plotting processes on ascending and descending scales is drawn from the Law of Seven, as found in the cosmology of G. I. Gurdjieff. The law in general, as Gurdjieff presents it, doesn’t name each point in the scale beyond its solfège title; his emphasis instead is on the differences in vibration and density between the points, and how they might be discerned in any process, and how we might navigate those differences. Gurdjieff does provide, however, one point-defined example of a very large descending scale: the Ray of Creation. In Gurdjieff’s cosmology, the macro-oriented Ray of Creation runs parallel to a micro-oriented alchemy that correlates with the transformation of substances as they fuel various aspects of being. In Muzoracle mythopoetics, the points within the Ray retain their connection to the cosmos, but are further defined in a way unique to the Muzoracle itself.

The Ray of Creation plots the ancestry of the cosmic beings of our world—galaxies, suns, planets, et al.—on a giant diatonic scale. The highest point in the scale—the pre-big bang do—vibrates the fastest; it is also the least dense, and levels of increasing density and slowing vibration cascade downward from it, through the cosmos to our relatively law-bound world. The fastest and finest, however, permeate the slow and coarse: the cosmic ancestry that we are contained within is contained within us as well. Through conscious effort, through becoming what we already deeply are, lies the possibility of individual evolution: the downward and outward flow of nature provides the possibility of inward and upward ascent. We can climb the ladder by virtue of being on the ladder. (It’s worth noting that the Ray of Creation is only our ray, the ray we can discern—one ray among who knows how many. How big was that bang? Further explorations of each of the scalepoints as they function in the Muzoracle can be found in the subpages under In Depth: The Solfège Dice, in the Table of Contents at left.)

The Ray of Creation plots the ancestry of the cosmic beings of our world—galaxies, suns, planets, et al.—on a giant diatonic scale. The highest point in the scale—the pre-big bang do—vibrates the fastest; it is also the least dense, and levels of increasing density and slowing vibration cascade downward from it, through the cosmos to our relatively law-bound world. The fastest and finest, however, permeate the slow and coarse: the cosmic ancestry that we are contained within is contained within us as well. Through conscious effort, through becoming what we already deeply are, lies the possibility of individual evolution: the downward and outward flow of nature provides the possibility of inward and upward ascent. We can climb the ladder by virtue of being on the ladder. (It’s worth noting that the Ray of Creation is only our ray, the ray we can discern—one ray among who knows how many. How big was that bang? Further explorations of each of the scalepoints as they function in the Muzoracle can be found in the subpages under In Depth: The Solfège Dice, in the Table of Contents at left.)

Chromatica. The Ray of Creation is plotted on seven notes, do-ti-la-so-fa-mi-re; these are the notes generated in a ternion, the notes of the diatonic major scale. However, the chromatic scale contains, and Solfège Dice exhibit, twelve scalepoints—what about the other five, the chromatic scalepoints?

Chromatic scalepoints do not have meanings separate from the diatonic scalepoints—they are instead mirror images of them. Here’s how and why.

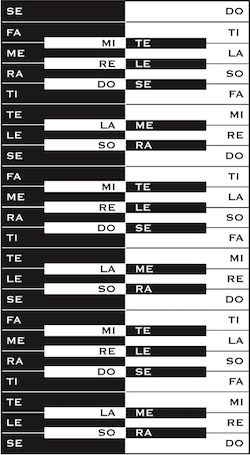

The twelve notes used in the Muzoracle are not drawn from the chromatic scale—they are drawn instead from two separate diatonic scales a tritone apart, one ascending while the other descends. The reason why two seven note scales give us only twelve points and not fourteen is that the two scales share two notes: ti and fa, which are themselves a tritone apart. The mechanics of this can be seen in the “Kingfisher’s Mirror” at right: on the right side of the mirror is a C Major scale, on the left, a major scale in F#/Gb. While the notes reflected in the mirror are always the same—la is always opposite me, for example—the scales are actually always in motion, one rising while the other falls. (Next time you’re playing a piano and catch a reflection of your hands in the lid, well… there you have it.)

This explains why, for example, do and se share the same meanings. In an ascending casting, do is the Point of Intention; se is actually a different do from a descending scale a tritone away, and is the Point of Inception. In a descending casting, the reverse is true: do descending is Inception, while se ascending is Intention. We would never find both do and se ascending in a casting and have Intention twice—because of the way casting works, diatonic and chromatic points always show up on opposite sides of the mirror.

It is significant that the interval that separates ascending and descending scales is a tritone, whose ratio is 5:7—the same dissonance that drives the Harmonic Engine. Whenever the Musician’s Die is rolled and a keycenter presents itself, we are not only invoking a scale based on organic elements arising in the harmonic series; we are also invoking its twin opposite, born of the same whirring mechanics.

Decrements. The diatonic scale is comprised mostly of “whole steps”: the ratios between the notes are either 8:9 or 9:10. Two of the intervals, however—the ones between mi and fa and ti and do—are “half-steps”: the distance between them is quite a bit less, at 15:16 or tighter. (This can easily be seen in the key of C on a piano: there’s no black key between E and F and B and C.) These naturally occurring smaller intervals—called decrements—are significant in that they bracket the naturally occurring tritone between fa and ti. They also figure prominently in mapping descending and ascending processes: successfully navigating mi to fa and ti to do requires a new sort of energy input, a kind of lessening for the shorter distance, perhaps in the form of finer material or a dissolving of attachments; a “shock,” as Gurdjieff put it.

In the Ray of Creation allegory, the decrement between do descending and ti, between Yang Absolute and our universe, is filled by “divine will,” the unfathomable descending force. Bridging the decrement between fa descending and mi, between the planetary, archetypal world of gods, goddesses, and dreams and the Earth, is the delicate, vibrating film that encases our beloved planet: organic life.